I spent a while reading aphyr’s “Call me maybe” series on distributed systems and was inspired to see if I could do a similar test on Hadoop. Hadoop is a distributed system, so it would seem reasonable to test which side of the CAP theory it achieves and whether it’s possible to experience data loss when using it.

I say Hadoop is a distributed system, it’s actually a number of different distributed systems. So initially, I’ll look at HDFS, which is the distributed filesystem built into Hadoop.

Caveats

A few things to point out. I’m not a computer scientist, and have very little idea of what I’m actually doing. It’s entirely possible that I’m doing it wrong, so comments are welcome. Secondly, while aphyr’s test framework Jepsen is great, I find trying to read and hack Clojure is a lot less fun than poking forks in my eyes, so I’ve reimplemented the bits that I need in Java. This has given me a test framework that’s much less flexible, maintainable and rigorous than Jepsen is, but hopefully should suffice for these purposes.

So, what are we trying to test? If you haven’t read the series on Jepsen, the basic premise is that we try and write some data to a distributed system, cause a network partition, and then see what happened. Systems aim to achieve either data consistency at the expense of availability, or vice versa (either side of the CAP theorum for very specific definitions of ‘Consistency’ and ‘Availability’). What often happens is that systems fail at achieving what they set out to achieve and end up chucking data away. This can cause problems if you’re using a distibuted system as a database, lock manager, queue etc.

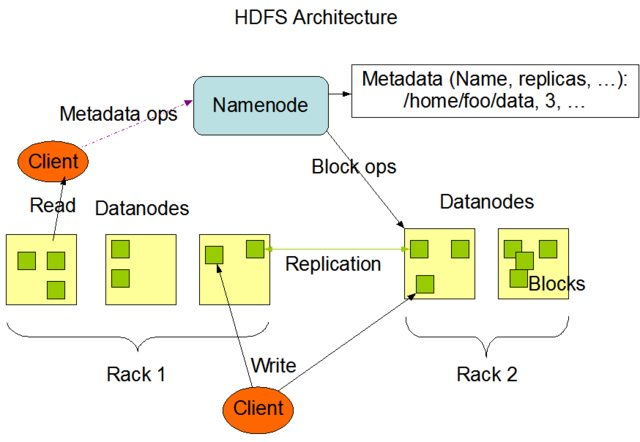

HDFS

In the case of HDFS, we have a filesystem. For all intents and purposes, this is a database, so lets see what happens if we try and write some data to HDFS when there’s a network partition. Hadoop’s HDFS architecture consists of a NameNode server, which keeps a state of the filesystem tree and the IDs of blocks that make up each file, and a number of DataNodes which actually store the blocks on their local storage. Blocks are typically replicated a number of times on different datanodes so that a block of data is resilient to a single datanode failure. The datanodes heartbeat to the namenode, so that that namenode is aware of all the datanodes that are currently alive in the cluster, and the replication status of each block.

Taken from the HDFS architecture documentation on Apache

Reading a file from HDFS involves a client contacting the namenode and getting a list of blocks and datanode locations of those blocks. The client then contacts those datanodes to actually fetch the data back. Writing a file to HDFS involves the client contacting the namenode to request writing to a particular path, the namenode responds with a list of datanodes and the client then connects directly to those datanodes to send the actual data.

The namenode is a fairly obvious single point of failure here, so there’s a mechanism to run a single standby namenode. This active/standby state is managed in Zookeeper. This also requires a service called a JournalNode, which is typically colocated with zookeeper and maintains a transaction log of HDFS reads/writes. Like zookeeper, the journalnodes maintain a cluster between them, and a namenode must be able to write to a majority of them for it to be operational.

It’s rapidly becoming clear that Hadoop isn’t a distributed system, but a complex array of different distributed systems all interacting. Yay!

Test Setup

My test setup is 5 LXC instances ranging called n1, n2, n3, n4 and n5 running Debian wheezy. I’m going to be using Cloudera’s distribution of Hadoop: CDH 5.0.3. We want full on distributedness of this, so I’m going to be using the high availability solution for this, so every instance will be an HDFS datanode, JournalNode and Zookeeper. n1 and n5 will be the namenodes (it turns out that you can currently have at most a single standby namenode).

I’ve put the hdfs-site.xml and core-site.xml files on a gist at https://gist.github.com/growse/98eeca316b37fb0d989b.

So, with all that out of the way, what are we actually going to test? Because HDFS is a filesystem, it should provide us with (amongst others) a guarantee that when we create a file, that file exists. This gives us a good starting point. Like Jepsen, the test framework will create 5 threads which will iterate a counter up to a certain value and try and write a file with a filename of that counter. Each thread will increment their counter by 5 and have an offset, so that thread 1 writes values 0,5,10,15 etc, thread 2 writes 1,6,11,16 etc. etc.

The code for the run method of the thread looks a little like this.

public void run() {

byte[] bytes = new byte[1024];

int value = offset;

while (value < count) {

LOG.info(String.format("Trying to write %d", value));

Path filepath = new Path(testpath, String.valueOf(value));

FSDataOutputStream stream;

random.nextBytes(bytes);

try {

stream = fs.create(filepath);

stream.write(bytes);

stream.close();

confirmedList.add(value);

} catch (IOException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

value += 5;

}

}

In this case, I’m actually writing 1,024 bytes of data to the file as well, this is simply so that the client has some work to do in creating a block and sending it to a datanode. If the write is reported to be successful, I add the value written to a synchronizedList called confirmedList. Finally, once all the threads have been joined, I can enumerate the filesystem to get the list of files written, and compare that to what was confirmed to have been written. Hopefully, these should be the same. Lets start out with no partitioning and 2000 writes as a quick sanity test:

[main] hdfstest.Runner: Creating /partitiontester/

[main] hdfstest.Runner: Starting Threads

[Thread-5] hdfstest.Runner$1HdfsWriterThread: Trying to write 0

[Thread-6] hdfstest.Runner$1HdfsWriterThread: Trying to write 1

[Thread-8] hdfstest.Runner$1HdfsWriterThread: Trying to write 3

...

[Thread-8] hdfstest.Runner$1HdfsWriterThread: Trying to write 1998

[Thread-7] hdfstest.Runner$1HdfsWriterThread: Trying to write 1992

[Thread-6] hdfstest.Runner$1HdfsWriterThread: Trying to write 1996

[Thread-7] hdfstest.Runner$1HdfsWriterThread: Trying to write 1997

[main] hdfstest.Runner: Finished

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 2000 total

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 2000 acknowledged

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 2000 survivors

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 0 acknowledged writes lost

It worked! Hurray.

Partition time!

Right, lets try and partition this. To achieve this, I’m using aphyr’s salticid to manage the cluster. In the old branch on the Jepsen repository there are some salticid tasks that can partition, heal, or slow down the network across the cluster nodes. This is simply done by adding iptables rules that block traffic between some nodes. In this case, I’m going to be partitioning n1 and n2 away from the rest of the nodes.

Lets see what happens.

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 200 total

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 194 acknowledged

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 194 survivors

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 0 acknowledged writes lost

So we couldn’t write everything, but at least it didn’t discard any data.

What actually happened was that the writes started to pause after the network partition. The active namenode was n5 and on the majority side, whereas the standby node n1 was on the minority side. Hadoop’s default settings means that things take a long time to fail. The active namenode took a little over 10 minutes to decide that the datanodes n1 and n2 were dead. This can probably be brought in by tweaking some of Hadoop’s dfs timeout configuration values.

What was more interesting was the behaviour of the datanodes on the majority side. There was a lot of log messages looking like this:

INFO org.apache.hadoop.ipc.Client: Retrying connect to server: n1/10.0.3.101:8020. Already tried 26 time(s); maxRetries=45

It seems that by default, when you write a block to a datanode, it tries to notify both the active and the standby namenodes over the IPC connection (port 8020). In this case (n4), it can’t reach the standby namenode, and blocks the client. The default IPC timeout is 20s, and the maxRetries value is set to 45. This would appear to indicate that if your standby namenode becomes unreachable, the datanodes block writes, by default, for 10-15 minutes.

Is it really great though?

The fact that the client blocked on all writes when the partition happened is a little concerning. I wondered if anything changed if both Namenodes ended up on the same side of the partition. This time, I partitioned n2 and n3 from the rest.

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 200 total

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 200 acknowledged

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 200 survivors

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 0 acknowledged writes lost

As before, there was a total pause while the minority datanodes were marked as dead followed by a continuation of the writes. So this time, the majority datanodes could see both namenodes, and yet they still blocked until the minority datanodes had been marked as dead. No data missing though, which is good.

NameNode failover

For the partitioning scenario where the two namenodes can no longer communicate, I’ve been deliberately putting the current active namenode on the majority side of the partition. What if it’s on the minority side?

INFO org.apache.hadoop.hdfs.server.blockmanagement.CacheReplicationMonitor: Rescanning after 30001 milliseconds

INFO org.apache.hadoop.hdfs.server.blockmanagement.CacheReplicationMonitor: Scanned 0 directive(s) and 0 block(s) in 0 millisecond(s).

WARN org.apache.hadoop.hdfs.qjournal.client.QuorumJournalManager: Waited 19015 ms (timeout=20000 ms) for a response for sendEdits. Succeeded so far:

[10.0.3.101:8485,10.0.3.102:8485]

FATAL org.apache.hadoop.hdfs.server.namenode.FSEditLog: Error: flush failed for required journal (JournalAndStream(mgr=QJM to[10.0.3.101:8485, 10.0.

3.102:8485, 10.0.3.103:8485, 10.0.3.104:8485, 10.0.3.105:8485], stream=QuorumOutputStream starting at txid 83496))

java.io.IOException: Timed out waiting 20000ms for a quorum of nodes to respond.

at org.apache.hadoop.hdfs.qjournal.client.AsyncLoggerSet.waitForWriteQuorum(AsyncLoggerSet.java:137)

at [......]

WARN org.apache.hadoop.hdfs.qjournal.client.QuorumJournalManager: Aborting QuorumOutputStream starting at txid 83496

INFO org.apache.hadoop.util.ExitUtil: Exiting with status 1

INFO org.apache.hadoop.hdfs.server.namenode.NameNode: SHUTDOWN_MSG:

/************************************************************

SHUTDOWN_MSG: Shutting down NameNode at n1/10.0.3.101

It dies. It’s gone. It’s decided that as an active namenode that can’t see a majority of the journalnodes, it has no business being alive.

What should happen now is that the standby namenode (actually the zkfc service) should notice in zookeeper that the namenode lock has been removed and therefore it should promote itself to active, fencing the standby namenode along the way. If you’ve configured sshfencing as your fencing mechanism, the other namenode appears to go into an infinite loop trying to ssh into the other namenode.

INFO org.apache.hadoop.ha.NodeFencer: ====== Beginning Service Fencing Process... ======

INFO org.apache.hadoop.ha.NodeFencer: Trying method 1/1: org.apache.hadoop.ha.SshFenceByTcpPort(null)

INFO org.apache.hadoop.ha.SshFenceByTcpPort: Connecting to n1...

INFO org.apache.hadoop.ha.SshFenceByTcpPort.jsch: Connecting to n1 port 22

WARN org.apache.hadoop.ha.SshFenceByTcpPort: Unable to connect to n1 as user hdfs

com.jcraft.jsch.JSchException: timeout: socket is not established

at com.jcraft.jsch.Util.createSocket(Util.java:386)

at [.....]

WARN org.apache.hadoop.ha.NodeFencer: Fencing method org.apache.hadoop.ha.SshFenceByTcpPort(null) was unsuccessful.

ERROR org.apache.hadoop.ha.NodeFencer: Unable to fence service by any configured method.

WARN org.apache.hadoop.ha.ActiveStandbyElector: Exception handling the winning of election

java.lang.RuntimeException: Unable to fence NameNode at n1/10.0.3.101:8020

at org.apache.hadoop.ha.ZKFailoverController.doFence(ZKFailoverController.java:522)

at [.....]

INFO org.apache.hadoop.ha.ActiveStandbyElector: Trying to re-establish ZK session

INFO org.apache.zookeeper.ZooKeeper: Session: 0x4474b1f60490006 closed

INFO org.apache.zookeeper.ZooKeeper: Initiating client connection, connectString=n1:2181,n2:2181,n3:2181,n4:2181,n5:2181 sessionTimeout=5000 watcher=

org.apache.hadoop.ha.ActiveStandbyElector$WatcherWithClientRef@4acf7fd0

INFO org.apache.zookeeper.ClientCnxn: Opening socket connection to server n5/10.0.3.105:2181. Will not attempt to authenticate using SASL (unknown er

ror)

INFO org.apache.zookeeper.ClientCnxn: Socket connection established to n5/10.0.3.105:2181, initiating session

INFO org.apache.zookeeper.ClientCnxn: Session establishment complete on server n5/10.0.3.105:2181, sessionid = 0x5474b1fb51c0003, negotiated timeout

= 5000

INFO org.apache.zookeeper.ClientCnxn: EventThread shut down

INFO org.apache.hadoop.ha.ActiveStandbyElector: Session connected.

INFO org.apache.hadoop.ha.ActiveStandbyElector: Checking for any old active which needs to be fenced...

INFO org.apache.hadoop.ha.ActiveStandbyElector: Old node exists: 0a096d79636c757374657212036e6e311a026e3120d43e28d33e

INFO org.apache.hadoop.ha.ZKFailoverController: Should fence: NameNode at n1/10.0.3.101:8020

INFO org.apache.hadoop.ipc.Client: Retrying connect to server: n1/10.0.3.101:8020. Already tried 0 time(s); maxRetries=1

WARN org.apache.hadoop.ha.FailoverController: Unable to gracefully make NameNode at n1/10.0.3.101:8020 standby (unable to connect)

org.apache.hadoop.net.ConnectTimeoutException: Call From n5/10.0.3.105 to n1:8020 failed on socket timeout exception: org.apache.hadoop.net.ConnectTimeoutException: 20000 mi

llis timeout while waiting for channel to be ready for connect. ch : java.nio.channels.SocketChannel[connection-pending remote=n1/10.0.3.101:8020]; For more details see: ht

tp://wiki.apache.org/hadoop/SocketTimeout

at sun.reflect.NativeConstructorAccessorImpl.newInstance0(Native Method)

at [....]

Caused by: org.apache.hadoop.net.ConnectTimeoutException: 20000 millis timeout while waiting for channel to be ready for connect. ch : java.nio.channels.SocketChannel[connec

tion-pending remote=n1/10.0.3.101:8020]

at org.apache.hadoop.net.NetUtils.connect(NetUtils.java:532)

at [...]

INFO org.apache.hadoop.ha.NodeFencer: ====== Beginning Service Fencing Process... ======

This looks pretty bad.

Meanwhile, the client is sitting there uttering quiet, panicky statements along the lines of “Connection refused” and “A failover has occurred”. This isn’t surprising. The previously active namenode has disappeared, and the other one hasn’t taken over yet, so as far as the client is concerned, nothing can be done. When you eventually heal the cluster and restart the failed namenode, you discover:

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 200 total

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 180 acknowledged

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 180 survivors

[main] hdfstest.Runner: 0 acknowledged writes lost

which is comforting, at least.

Conclusions

It seems that HDFS does a pretty good job of holding onto data that you write to it, but this is at the expense of availability. What’s unexpected is that in the event of a datanode failure, IO events to the whole cluster appear to pause until that datanode either comes back or is declared dead.

The defaults shipped with CDH5.0.3 appear to give around a 10 minute time period before actually declaring a datanode as dead. This means that you will potentially block clients for up to 10 minutes in the event of a prolonged event. On the one hand, this is desirable. If a datanode reboots, you don’t want the namenode to suddenly eat up network IO trying to replicate blocks that are now presumed to be unavailable. On the other hand, losing availability for an extended period of time due to a single failure feels a bit icky.

Finally, in my configuration, a standby namenode which partitioned away from the active namenode so that the active could no longer see a majority of the journalnodes failed to promote itself to active. I’m going to re-check my configuration, but this seems either like a bug, or a fundamental design flaw in the sshfence mechanism.

There’s a bunch more things I want to test here. The namenode/journalnode interaction is potentially interesting, especially when the namenodes become partitioned from the journalnodes. Similarly interaction between these components when they may become partitioned from zookeeper may also be worth investigating. We already have a reasonable understanding of how zookeeper works, so I’m fairly happy with that bit.

All testing and configuration suggestions are welcome.

Updates

July 22nd @fwiffo suggested that if I’ve got zookeeper and a QJM, I shouldn’t really be using ssh for fencing the dead namenode. Instead, this is handled automatically by zkfc. I changed the fencing method to shell(/bin/true) (which effectively means “don’t bother to fence”) and reran the test. This time, the majority side namenode promoted itself without issue.

I couldn’t find anything in the Cloudera documentation about this, so I’ll drop them a note and get their view, and see if the documentation could be updated.